- History

- Yoo Hong Jun / Culture Critic

-

- 1949

- Born in Seoul Korea.

- 2004

- Served as Cultural Heritage Association President

- 2018 ~

- Named Endowed Chair Professor of Myongji University Department of Art History

|

- The Warm and Abundant World of Bowls - A Personal View on the Ceramics of Gyung Kyun Shin

- First Meeting Four or five years ago when I was serving as the Cultural Heritage administrator, there was an excavation of an ancient tomb on the Goheung peninsula in South Jolla Province. I went down to this southern most tip of Korea for an onsite visit. While I was down there, I decided to look around the Buncheong kiln and dolmen sites in Woondaeri. Bucheong is pottery decorated with white slip and covered with a pale bluish-green glaze. The sight of the dolmen gathered together in the midst of pine of trees was a scene out of ancient times. However, when I arrived at the kiln sites, I could not believe my eyes.

When I went there 20 years ago with then Jeon Nam University professor Taeho Lee, the fields were filled with Buncheong fragments. They were mostly from white clay Buncheong bowls, the ones highly regarded by the Japanese. In the 16th century, white clay Buncheong was produced in Woondaeri and transported to Japan through Boseong. That is how I knew that this area was a very important ruin in Korean art history. But as I stood there, there was not a single shard left. I asked the local cultural heritage personnel what had happened, and he said that from about ten years ago Japanese tourists came in waves as a part of ceramics and kiln site exploration tours. And soon after that began, all the shards disappeared.

I just could not believe it. I was in such shock and loss that I stood there staring up at the sky. As I stood there, a man approached me and said, “There are untouched layers upon layers of fragments in that mountain,” pointing to the mountain in front of us. Then he introduced himself and said, “My name is Gyung Kyun Shin. I make ceramics here.” I hurriedly followed him to the place he was talking about. After we traveled a certain distance into the mountain, he stopped and dug into the earth with his bare hands. There, as he had said, were layers of Buncheong fragments. Surprised and elated, I asked him how many more similar places there were. And he said that they were spread out throughout the mountain.

I sincerely thanked this ceramicist. He knew something that even the local official in charge did not know. He had done the cultural heritage investigation for us. As I was getting in my car, he pointed to an area and said that it was where his kiln was. It seemed that he wanted me to visit it. I thought about visiting for a moment but then decided to decline his invitation for another time. Now that I think of it, I declined because I did not know who Gyung Kyun Shin was, and I did not want him to use my visit as a marketing tool for his kiln. Instead, out of politeness, I asked him a few questions.

“How does a man from Gyeongsang Province come all the way here to make ceramics?”

“The clay here is good.”

“Do you usually make Buncheong ceramics?”

“I make Buncheong, white porcelain… I make what I want.”

“Then do you mostly make tea bowls?”

“I make tea bowls, large round bowls… I make what I want.”

His answers were not ordinary. It was evident that he did not appreciate my superficial questions. I could sense his individuality from the way he spoke. As I was getting into the car, he approached me and in a low voice, said one more thing.

“Administrator, you know ceramicist Jung Hee Shin, don’t you?”

“Of course, I do. He is the leader in making tea bowls.”

“I am his son.”

“Is that so.”

In hindsight, Shin probably told me his name in the hopes that I would recognize it since at the time was I writing many art reviews. But when I did not, he reluctantly told me his father’s name so that I would remember him in the future. When I met Shin, I was actually only concerned about how I would restore the kiln site. I did not have the time to think of a ceramicist’s work. As soon as I got in the car, I called the historic landmark director and had him start the process of designating Woondaeri a national historic landmark. (Thereafter, we could not obtain the agreement Woondaeri landowners so it could not be designated as a landmark. In order to circumvent this, the government tried to purchase the land but I have not been able to check on its progress.)

The Artist and the Critic I heard Gyung Kyun Shin’s name once again in 2005 during the APEC summit meeting held in Busan. His ceramics were used to serve heads of state and some 40 of his works were displayed throughout the meeting halls. Not only that, I read an article that his kiln and workshop, Janganyo, was designated as a cultural visitation site for first ladies during the meetings. I was excited to see how much the Korean government’s protocol office had developed in terms of cultural foreign affairs. I always felt that this was the way it should be done. (A few years ago, all the chinaware used during the Dutch queen’s visit to Korea was Royal Copenhagen, brought in from Denmark.)

However, the first time I saw Shin’s ceramics pieces was in 2006 during his exhibit at Gallery Hyundai’s Dugahun in Seoul. I did not look very critically but I felt that the varied colors of his everyday pottery and the large bowls had a modern style to them. I especially had a good feeling as I felt the warmth of his pieces. As always, I told the president of Gallery Hyundai my thoughts about Shin’s ceramics. She told me that his ceramics had this warmth because they come from a wood fire kiln.

I took this opportunity to learn more about Shin’s experience. I learned that he had already had five exhibits and he was not new in the world of ceramics. He had three exhibits in Busan, his hometown, and one in Daegu and Seoul each. So as a ceramicist, he had already secured a position. Janganyo was already relatively well known for its ceramics and everyday pottery – enough to have a steady following.

Nonetheless, there was never a real critique or review of Shin’s work. Therefore, many people knew of Shin as the person behind Janganyo but it was difficult to pinpoint the artistic characteristics and value of his ceramics. And it was not like Shin had written about his ceramics, either. He does not like to be interviewed by the media and when he does give an interview, he talks about his life as a ceramicist rather than about his work. And even then, he would say things like, “Art is simple,” or “Art is life itself,” or “I just want to be free.” It is actually not the artist’s responsibility to talk about the characteristics of his work. It is the critic’s responsibility.

Most people think of a critique or review as an evaluation, but it has a more important role than this. The critic is the link between the artist and the audience – sometimes speaking on the side of the artist and sometimes asking questions from the side of the audience. Therefore, for an artist, it is ideal to have such a person close by from start to finish. But Shin has not had anyone around him to critique his work. (I later found out that his wife was more than adequately plays this role.)

It is not to say that I will take on this role. I am a part of the audience. I saw his works at Dugahun and then visited Janganyo to see his works there. I was once an art critic but now I do not live that life and am in no way a ceramics expert. But I am publicly writing what I felt about Shin’s work in the hopes that I may be a catalyst to narrowing the gap between the artist and the audience.

A Modern Development on Traditional Technique Korean ceramics is divided into traditional and modern ceramics. However, I feel that in order for Korean ceramics to develop further, we must be free from this division. Traditional ceramics are the green celadon of the Goryeo Dynasty and the Buncheong and white porcelain of the Joseon Dynasty. Modern ceramics are modern art expressed in the form of ceramics. Some charge that university art professors created this division in order to emphasize their area of study. Some even say that those in traditional ceramics are not ceramic artists but just mere potters.

One cannot say that traditional ceramics is completely faultless for this bias. Ceramics is just like other crafts in that artistic value must blend in with technique. If one focuses on the technique of firing, then he is just a potter. Traditional ceramicists would not have experienced this insult if they had embraced modern ceramics while staying grounded in traditional ceramics like Yik Yung Kim, known for his white porcelain, and Kwang Cho Yoon, known for his Buncheong.

Then is Gyung Kyun Shin a traditional ceramicist or a modern ceramicist? His techniques are those used in making white porcelain and Buncheong. However, if you take a look at the forms of his ceramics, they follow a modern technique. When he was fifteen years old, he began his apprenticeship in traditional ceramics under his father, Master Ceramicist Jung Hee Shin. Then in high school, he built his experience in modern ceramics. So for him, there really was no need to make a differentiation between traditional or modern ceramics. This is his great strength.

Shin began in tradition but his inclinations are for modern ceramics. He continuously tests clay to see how he can recreate the white porcelain and Buncheong of the Joseon Dynasty for our generation. For example, white porcelain is made from white clay called kaolin. There is no iron in this white clay. If there is even just 0.1% iron present in the clay, the ceramics will not be white. The fire causes a chemical reaction with the iron so the ceramics have a slight yellow or green tint. Iron oxide will cause the pieces to be yellow while ferric oxide will cause it to be green. Shin uses this property to his advantage to create white porcelain with a subtle hint of yellow or green. Traditional ceramicists insist on using white clay that is totally free of iron but Shin expands the scope of white porcelain and is clearly on his way to redefining it.

There are many ways to express designs in Buncheong - through inlay, flowers, brush paint, design with iron glaze, white slip, etc. However, if you look at the base glaze of Buncheong, they are usually green, brown, black, or gray. The color depends on the type of clay that is used. Shin uses the different characteristics of clay to create new colors such as green, mustard, olive green, khaki, and chocolate.

Shin creates all the colors in what they call in modern ceramics chromaticity. But there is an important difference here. He does not use any chemicals in his glazes to create these colors. He uses the glaze making techniques of traditional ceramics to make his glazes. Therefore, all his glazes are natural. Sometimes they are made from feldspar and wood ash or from leaf compost. His wood ash glazes are made from pine, oak, elm, or straw. It is in this way Shin is keeping his foundations rooted in traditional techniques while expanding his expression into modern ceramics.

The Appeal of Gyung Kyun Shin’s Ceramics – Warmth and Natural Colors Ceramics is based on a mixture of art and technique. The fact that Shin has found a new technique to express his work while staying true to tradition means that he has fulfilled an artistic direction. The way in which Shin uses these techniques to express beauty is the appeal of his ceramics.

I think that the first appeal of Shin’s ceramics is texture. His ceramics are as smooth as the human skin and are warm to the touch. This might be my subjective opinion but one thing is certain. The texture of his ceramics is the greatest appeal of his work.

Just before Shin’s exhibit at Gallery Hyundai, ceramicist Young Jae Lee had an exhibit. Lee displayed ceramics in six unique colors such as dark green, dark brown, and light green. While her modern design and colors were commendable, they were very cold to the touch.

In contrast, Shin’s ceramics were warm and smooth and gave a sense of naiveté. .If Lee’s work has a European feel, Shin’s work has a Korean feel. I am not saying one is better than the other. I am just pointing out how different the texture could be despite the similar color.

Then why is there this difference? More than anything, it is because Lee has a gas kiln while Shin fires all his work in a wood fire kiln. One is mechanical while the other is natural. Shin probably insists on wood fire kilns not because it is tradition but because if his work was fired in anything else, it would not have this same warm texture. Warmth– this is the most important feature of Korean ceramics.

The second feature of Shin’s work is color. He showcased many different colors through his work, demonstrating his broad ability to express himself. Of these colors, green and dark brown are Shin’s colors. Even if it is the same green, there is variation of dark and light, shades and tints. I cannot articulate it in a word but it is the green found in nature like grass. There are also many shades of brown but it is the brown found in nature like the earth. Just as the brown earth and green grass are in perfect harmony in nature, I feel this harmony when I see Shin’s brown and green ceramics together.

I hope Shin would delve further into creating green and brown ceramics. I am not saying that he should take a DIS color chart and research each color. As there are many shades and tints of green and brown in nature like the deep brown fertile soil to the light brown sand on the riverbank or the bright green valleys of Gyeongju, I believe that if Shin thinks of these places as he glazes his ceramics, the end product would bring him ever closer to the true color of nature he has been pursuing. I am not saying Shin should battle with the canvas as Hwan Gi Kim did in his work Where Would We Meet as What when he placed the countless dots on the canvas. Rather Shin might let his creativity flow as he thinks of singing birds and the ocean as he “places the dots”.

Shin’s ceramics, whether they are green or brown, have a subtle elegant variation in color in each piece. There is a natural harmony between light and dark. There is no tension. This is only possible in a wood fire kiln where this phenomenon is a coincidence but a necessity for color variation. Individual tastes are different. Some enjoy the color variation while others prefer a single tone. But one thing is for sure, this warmth and natural variation is not possible with a machine. It is only possible with someone who follows the principles of nature. Koreans appreciate this warmth.

I want to emphasize my point with a few examples. No matter how good they say a pressure rice cooker is, nothing compares to the rice cooked in the large iron pot on the wood fired oven. If this goes back too far in time, it is like the difference between cooking a steak in the microwave and grilling it over a barbecue.

The Abundant and Dependable Bowl In order to discuss Gyung Kyun Shin’s world of ceramics, we still need to talk about design and shape. Four factors must be taken into consideration in order to review a ceramics piece: color, texture, pattern or design, and shape. Of these, Shin does not put too much weight on patterns and designs. And it does not seem like he puts much effort into it either. The intriguing color variations are like the pattern so another pattern would actually interfere. I think he may have purposefully avoided patterns. No patterns might be his concept of a pattern.

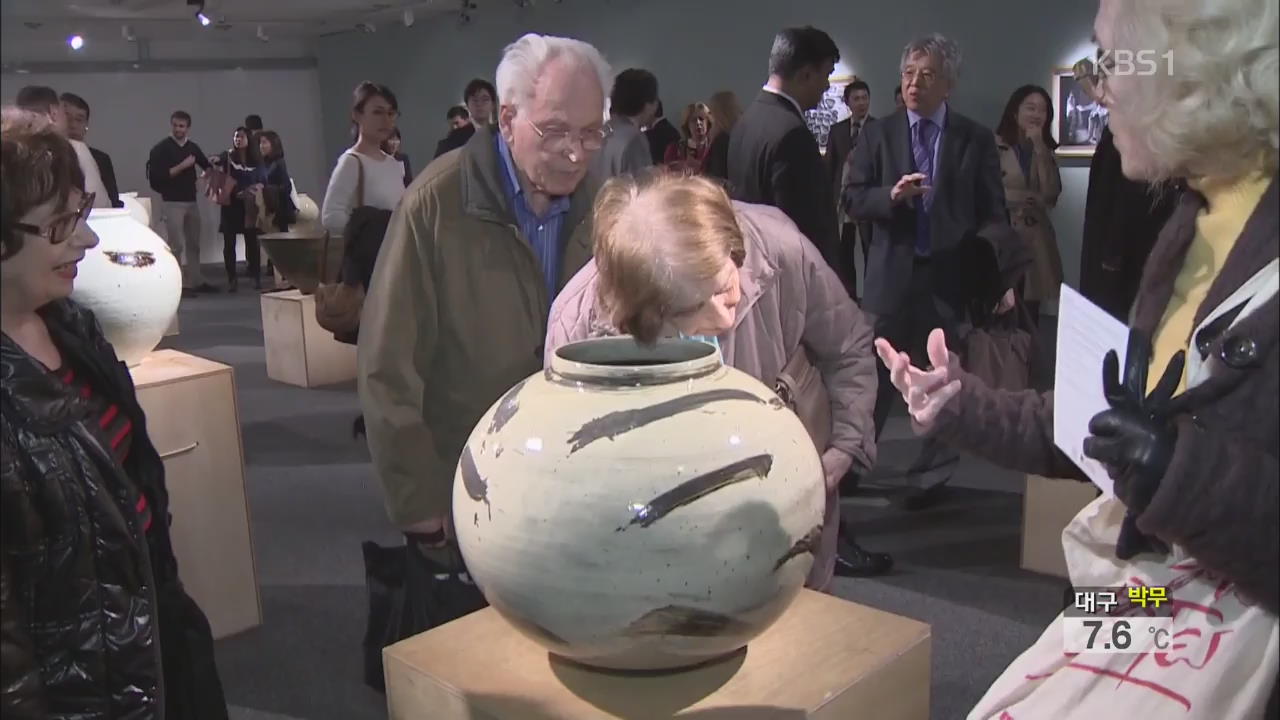

Regarding the shape of his ceramics, there is nothing Shin cannot make and there is no shape he has not made. However, of his pieces, I believe the large bowl is the best representation of his work. Its form gives an abundant and dependable feeling and with its smooth and warm texture, any color would be perfect. Moreover, the large bowl matches Shin’s personality and his creative artistic ability. That is why I see Shin’s uniqueness in the bowl.

Shin’s bowl is different from any other ceramicist. First, there are many variations in the finishing. Just as there are variations in the color, there are variations on the surface. There are intriguing ridges on the surface. But there are not forcibly there; it is there naturally, another great appeal. This is probably because he uses a wooden potter’s wheel and it might be the very reason Shin insists on it.

During the Japanese colonial rule, a ceramics researcher visited Korea to research how Korean ceramics were so natural. This researcher went to a kiln in a remote part and asked the person turning the potter’s wheel where he might find the master. That potter did not stop turning the wheel but rather just motioned to the interior of the house with his chin. That is when the researcher realized it was the potter’s wheel that gave Korean ceramics their naturalness. It does not start from a perfectly balanced wheel with subsequent efforts to try to give it a natural feel. The ability to give everything up to things that are natural to have a calmness within the soul is the secret of Korean ceramics. Shin’s wooden potter’s wheel has the same effect on his work as the kiln has on the glaze – it controls the result.

Shin’s bowls go well with his other pieces. It can be a teapot or a symbolic object. They all go together. This is because of the special feature and appeal of a bowl. It is like a tall pine tree in the yard. It goes well with other plants in the yard. It is like the large white porcelain jar that embraces everything else around it.

Many people know the abundant feel of the large white porcelain jars but few know the beauty of the bowl. Whether it is in the East or West or the past or present the basis for all dishes is the bowl. There must be a bowl in order to complete everyday cookware. Despite the changes the bowl has gone through throughout the ages, the large bowl is probably its best representation. Many ceramicists have made large bowls but Shin’s bowls are different from anybody else. And he is able to express it in his many unique colors with his own style. Whether they are white, green, or brown, they all have abundance and warmth. That is why if anyone asks me to summarize Shin’s ceramics, I would say it is the world of warm and abundant bowls.

|